Para quem ainda não teve a oportunidade de ver a prova de inglês da terceira fase deste ano, seguem os textos das tarefas abaixo.

Translation Part A

It was once the custom for British ambassadors to write a valedictory dispatch at the end of their posting. In contrast to the utilitarian style of daily diplomatic reporting, ambassadors were expected to spread their wings with candid comment on the country they were leaving, larded, where the wit was willing, with humorously pungent observations on the character of the locals. The best were distributed throughout the diplomatic service for the enlightenment and amusement of its ranks.

These were usually pretty sensitive and might be construed as a slight abroad were their contents divulged beyond the Ministry’s portals. Some missives were deemed so delicate that their circulation was restricted for fear of leaks. Bidding farewell Sir Ivor Roberts dared ask: “Can it be that in wading through the plethora of business plans, capability reviews, skills audits… we have forgotten what diplomacy is all about?”

Whether written with quill, typewriter or tablet, a key requirement has even been the ability to render incisive judgement, with style and wit.

Christopher Meyer. How to step down as an ambassador – with style. The Daily Telegraph. August 7th 2015.

Translation Part B

A empreitada de implantação da cultura europeia em extensor território, dotado de condições naturais, se não adversas, francamente antagônicas à sua cultura milenar, é, nas origens da sociedade brasileira, o fato dominante e mais rico em consequências. Trazendo de países distantes nossas formas de convívio, nossas instituições, nossas ideias, e timbrando em manter tudo isso em ambiente muitas vezes refratário e hostil, somos ainda hoje uns desterrados em nossa terra. Podemos enriquecer nossa humanidade de aspectos novos e imprevistos, aperfeiçoar o tipo de civilização que representamos, mas todo o fruto de nosso trabalho ou de nossa preguiça parece participar de um sistema de evolução próprio de outro clima e outra paisagem.

É significativo termos recebido a herança proveniente de uma nação ibérica. Espanha e Portugal eram territórios-ponte pelos quais a Europa se comunicava com os outros mundos. Constituíam uma zona fronteiriça, de transição, menos carregada desse europeísmo que, não obstante, retinha como um patrimônio imprescindível.

Sergio Buarque de Holanda. Raízes do Brasil. 3ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1956, p. 15-16.

Summary

The times in which we live are epoch-making. Literally. Such is the scale of the changes humans have wrought of late that our world has been altered beyond anything experienced hitherto. Our planet is now crossing a geopolitical boundary, and we are the change-makers.

Millions of years from now, a stripe in the accumulated layers of rock on Earth’s surface will reveal our human fingerprint, just as we can discern evidence of dinosaurs in rocks of the Jurassic, the explosion of life that marks the Cambrian or the glacial retreat scars of the Holocene. Our imprint will be revealed by species going extinct by the score, sharp changes in the oceans’ chemistry, depletion of forests and encroachment of deserts, shrinking of glaciers and the sinking of islands. Geologists of the far future will detect in fossil records a diminishing array of wild animals offset by an upsurge of domesticates, the baleful effects of detritus such as aluminium drink cans and plastic carrier bags, and the noxious smudge of mining projects laying waste the oil sands of north-western Canada, revolving 30 billion tonnes of earth each year – twice the amount of sediment discharged from all the rivers in the world.

In acknowledgement that humanity has become a geophysical force on a par with the earth-shattering asteroids and planet-cloaking volcanoes that defined past eras, geologists are dubbing this new epoch the Anthropocene. Earth now ranks as a human planet. We determine whether a forest stands of is razed, whether species survive or become extinct, how and whither a river flows, the temperature of the atmosphere, even. We have become the most manifold big animal on Earth, followed by those we breed to feed and serve us. Nearly half the planet’s land surface is now used to grow our food, and we control three-quarters of the world’s fresh water. Prodigious times, indeed. In the tropics, coral reefs dwindle, ice melts apace at the poles while the oceans are emptying of fish at our doing. Entire islands are submerging under rising seas, just as naked new land emerges in the Arctic.

It has become the business of science journalists to take special note of reports on how the biosphere is changing, and research is hardly in short supply. Study after study plot changes in butterfly migrations, glacier melt areas, ocean nitrogen levels, wildfire frequency… all linked by a common theme: the impact of humans. Scientists have described the multifarious ways humans are affecting the natural world. Climate scientists tracking global warming have forewarned of deadly droughts, heatwaves and gathering sea-level rise. Conservation biologists have envisaged biodiversity collapse to the point of mass extinction; marine biologists deplore “of plastic garbage” roaming the seas; space scientists debate the destiny of all the junk up there menacing our satellites; ecologists denounce deforestation of the last intact rainforests; agro-economists raise the alarm about deserts engulfing vast tracts of fertile soil. Every new study hammers home the extent to which our world is changing. Humanity is shaking it up. And people across the globe can hardly be in any doubt about the environmental crisis we set in motion. All this is deeply troubling, if not overwhelming.

Dire predictions abound as to our future on Earth. At the same time, nonetheless, we should not disparage our triumphs, our inventions and discoveries – how scientists find novel ways to improve plants, stave off disease, transport electricity and forge new materials. We can be an incredible force of and for nature. Humans have the power to heat the planet further or to cool it down, to eliminate species and to engineer new ones, to re-sculpt the terrestrial surface and to fashion its biology. No part of this planet is untouched by human hand – we have transcended natural cycles, altering physical, chemical and biological processes. We can craft new life in a test tube, resurrect extinct species or grow replacement body parts. We have invented robots to be our drudges, computers to expand our brains, and a new ecosystem of communication networks. We have redrawn our own evolutionary pathway with medical advanced that save those who would otherwise die in infancy. We are supernatural: we can fly without wings and dive without gills; we can survive killer diseases and be resurrected after death.

The realisation that we wield such planetary power requires a major shift in perception, one that topples the scientific, cultural and religious philosophies that define our place in the world, in time and in relation to all other known life. Mas was once framed at the centre of the Universe. Then came Copernicus in the 16th century, who put Earth in its place as just another planet revolving around the Sun. By the 19th century, Darwin had reduced man to just another species – a wee twig on the grand tree of life. The paradigm has swung round again, though: man is no longer just another species. We are the first to knowingly reshape the Earth’s biology and chemistry. We have become vital to the destiny of life on Earth. The Anthropocene throws up unprecedented challenges, as we have already begun to tilt global processes out of kilter. In some cases, miniscule further changes could spell disaster; in others, a fair degree of leeway remains before we face the consequences.

The self-awareness implicit in recognising our power requires us to question our new-found role. Are we just another part of nature, doing what nature does: reproducing to the limits of environmental capacity, subsequently to suffers a sudden demise? Or shall we prove the first species capable of curbing its natural urges, and modulating its impact on the environment, such that habitability on Earth can be maintained? Should we treat the rest of the biosphere as an exploitable resource to be plundered at will for our pleasures and needs, or does our new global power imbue is with a sense of responsibility over the rest of the natural world? The Anthropocene – and our very future – will be defined by how we reconcile these opposing, interwoven drives in the years to come.

Gaia Vince. Humans have caused untold damage to the planet. The Guardian. September 25th 2015. In: <www.theguardian.com>

Composition

History consists of a corpus of ascertained facts. The facts are available to the historian in documents, inscriptions and so on, like fish on the fish monge’s slab. The historian collects them, takes them home, and cooks and serves them in whatever style appeals to him. Acton, whose culinary tastes were austere, wanted them served plain. In his letter of instructions to contributors to the first Cambridge Modern History, he announced the requirement “that our Waterloo must be one that satisfies French and English, German and Ducth alike”.

E.H. Carr. What is history? 2nd Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987, p. 9 (adapted)

When history is mobilised for specific political projects and sectarian conflicts; when political and community sentiments of the present begin to define how the past has to be represented; when history is fabricated to constitute a communal sensibility, and a politics of hatred and violence, we [historians] need to sit up and protest. If we do not, then the long night will never end. History will reappear again and again, not just as nightmare but as relieved experience, re-enacted in endless cycles of retribution and revenge, in gory spectacles of blood and death.

Neeladri Bhattacharya, quoted in Willaim Dalrymple. Trapped in the ruins. The Guardian. March 20th 2004.

Compare and discuss the views of history expressed in the two quotes above, illustrating your discussion with appropriate examples.

Cheers!

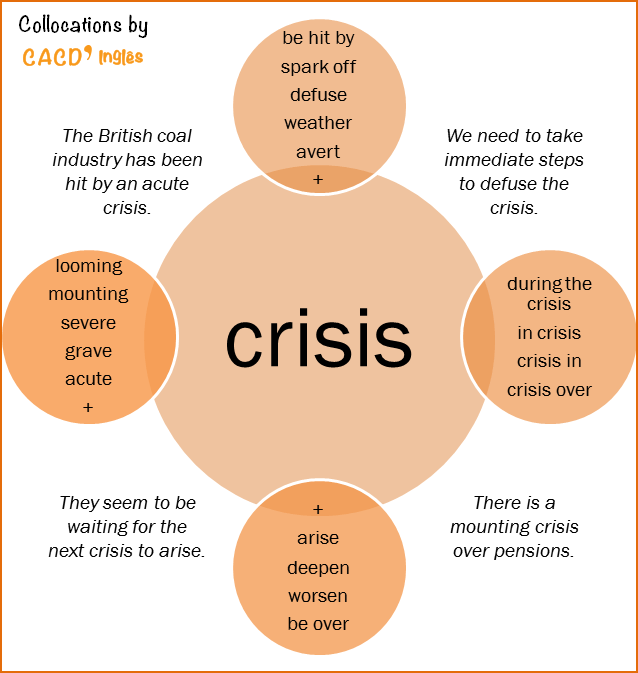

Source: Oxford Collocations Dictionary

Source: Oxford Collocations Dictionary